Summarization in NLP

Among the many challenges faced by Natural Language Processing (NLP) researchers today, the summarization task is perhaps one of the most difficult to crack. For one, summarization is difficult even for humans. It requires a comprehensive understanding of the text at hand and an acute ability to tune into the important messages and out of the unimportant ones.

The summarization task in NLP is split into two separate ones: abstractive and extractive summarization. As you can guess from their respective adjectives, abstractive summarization involves re-writing the given text into an original summary while extractive summarization involves choosing key sentences in the given text to serve as the summary.

Both tasks require the model to “understand” the main point of the text but they differ in that abstractive summaries have to involve some form of a generation model, while extractive summaries do not. In fact, the extractive summarization task is regarded a binary classification problem involving sentence-level embeddings.

Today, I want to focus on extractive summarization and how to train a Transformer-based model for this task.

Extractive Summarization

Word Vectors & NLP Models

If you were given a long piece of text and asked to pick out its three most representative sentences, how would you approach the problem? You would probably read the whole thing, identify the thesis statement and two other sentences that provide the best evidence for the thesis. Simple! But how do you get a machine to do the same?

Obviously you can’t. Current state-of-the-art models do not actually understand and interpret text. But it can mimic human understanding to a surprising nearness by learning patterns and distributions in the training data.

Because machines don’t actually understand the text and language that humans use, we numericalize text data into numbers, most often into multi-dimensional vectors that represent “meanings” of words. The primary goal of NLP models today is to formulate vectors that best capture the complexities of our natural language.

The standard for the “best” word vectors will depend on the task. For instance, if you’re training a general language model, you probably want the vectors of similar words to occupy similar spaces in the vector space. If you’re training for a specific task, such as identifying which part-of-speech each word is, you might want a model that maps words with the same parts-of-speech to similar spaces.

By far the most popular NLP model used in research today, the Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT), developed by Google, has been a game-changer in the field since its inception in 2018. BERT outperforms traditional NLP models, largely because it most accurately learns from the training data, producing the best word embeddings that are dynamic and context-aware.

I won’t get into the technical details of why BERT is superior to its predecessors, but its advantages stem from using a computationally fast attention mechanism and from being a bi-directional model, meaning it uses information from both sides of a word to calculate its embedding.

So how such can we use BERT for extractive summarization?

BERT for Sentence-level Classification Tasks

The extractive summarization task is treated as a standard binary classification problem. Sentences are either included in the model (label 1) or not (label 0). The overall model architecture thus involves two parts:

- An encoder that outputs embeddings

- A classifier that outputs labels 1 or 0

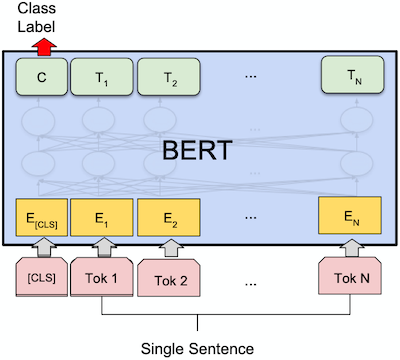

Because we’re classifying sentences and not words, we must have a sentence-level embedding. To derive such sentence-level embeddings from BERT, we use the embedding of the special token [CLS] (which stands for classification) that is added in front of each sentence input. Refer to the image below.

No one truly understands what the [CLS] token represents, but probes have shown that this token “pays attention” to all the other tokens in the sentence, which is why researchers believe it is an appropriate single-vector representation of the sentence. The last hidden layer of the [CLS] token is used as the sentence-level embedding.

This sentence-level embedding is then passed to the classifier which outputs a prediction label.

In simple terms, training goes something like this…

- Input

[CLS]+input_sentenceto the BERT model - Get the sentence-level embeddings using the

[CLS]token - Pass the embedding from (2) to the classifier to output a prediction label, which is used to calculate loss and train the parameters in the model to your task.

The classifier can be a simple logistic regression model or more complex, such as a Transformer encoder.

BERT for Extractive Summarization: BERTSUM

Issues

We’ve looked at the basic procedures for sentence-level classification problems in BERT. However, the extractive summarization task presents a unique problem: the input is a whole document, comprised of several sentences, from which we must somehow choose k sentences as our extractive summary.

For other sentence-level classification problems such as sentiment classification, a single sentence is used as input and the model labels this single sentence. However, extractive summarization requires the model to compare and contrast several sentences and then select a certain k number of them as the summary. This means that the input cannot be a single sentence, as it usually would be. The input must be the whole document, a collection of sentences, but we must still derive an embedding vector and label for each sentence.

Solutions

As a solution, the authors of BERTSUM resorted to extending BERT by inputting the whole document as a single sequence, separated by [CLS] and [SEP] tokens, resulting in the following input sequence structure for a document with n number of sentences:

[CLS] + sentence 1 + [SEP] + ... + [CLS] + sentence n + [SEP]

To ensure the model recognized the sentence boundaries, interval segmentation embeddings were also added to the model (green boxes in the diagram below). For an overall view of the architecture, take a look at the diagram below, taken from the original paper.

Once each sentence-level embedding is obtained from the [CLS] token, a classifier is used to obtain a score for each sentence. The k sentences with the highest scores (or lowest loss ) are chosen for the final summary. In their paper, the authors use an inter-sentence Transformer with two layers as the classifier.

These predictions are compared to the gold label, and binary classification entropy is used as the loss function to fine-tune the model.

To summarize, BERTSUM overcomes some of the problems faced in extractive summarization by…

- Extending the input to multiple sentences: whereas BERT usually accepts 1 to 2 sentences as input, BERTSUM accepts several sentences as input, each one separated by the

[CLS]token. - Adding segment embeddings: to make sure the model recognizes sentence boundaries, segment embeddings are added in addition to the existing positional embeddings.

Training & Results

This BERTSUM model is fine-tuned on several datasets, including the CNN/Daily Mail new highlight dataset, the New York Times Annotated Corpus, and XSum. The model is evaluated using ROUGE-2 scores.

The model outperforms existing Transformer-based models on all tasks. Below are ROUGE F1 results from the CNN/Daily Mail dataset:

Limitations of BERT for Extractive Summarization

Despite the state-of-the-art results, BERTSUM is not without its limitations. I believe there are two main shortcomings to this model.

First, because of computational limitations, the length of the input document must be curbed to 512 tokens. This means that the model cannot be used in most practical applications, as real-world documents obviously exceed this limit.

Secondly, the role of the [CLS] token in BERT remains ambiguous. Although initial research suggested that this special token did retain and learn information from all other tokens in the sentence, more recent research has shown that it is not an accurate representation of the sentence and should be used with caution.

Suggestions for Further Research

On this note, further research could involve creating models with more efficient attention mechanisms or with less numbers of parameters to alleviate the calculation burden, allowing for longer document inputs. Also, more efficient and effective methods of acquiring sentence embeddings could lead to gains in performance.

Much of research today is already addressing some of these issues. Models such as Big Bird or Longformer attempt to allow longer input sequences by modifying the attention mechanism, while models such as Sentence-BERT attempt to attain accurate sentence embeddings in an efficient manner.

How will such models fine-tuned to extractive summarization measure up to the original BERTSUM? Time for some experiments!

References

- BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding, Devlin et al., 2018.

- Text Summarization with Pretrained Encoders, Liu and Lapata, 2019.